Why Tech Companies Design Products With Their Destruction in Mind

Apple develops a robot to take iPhones apart; firms also design devices with simple disassembly in mind

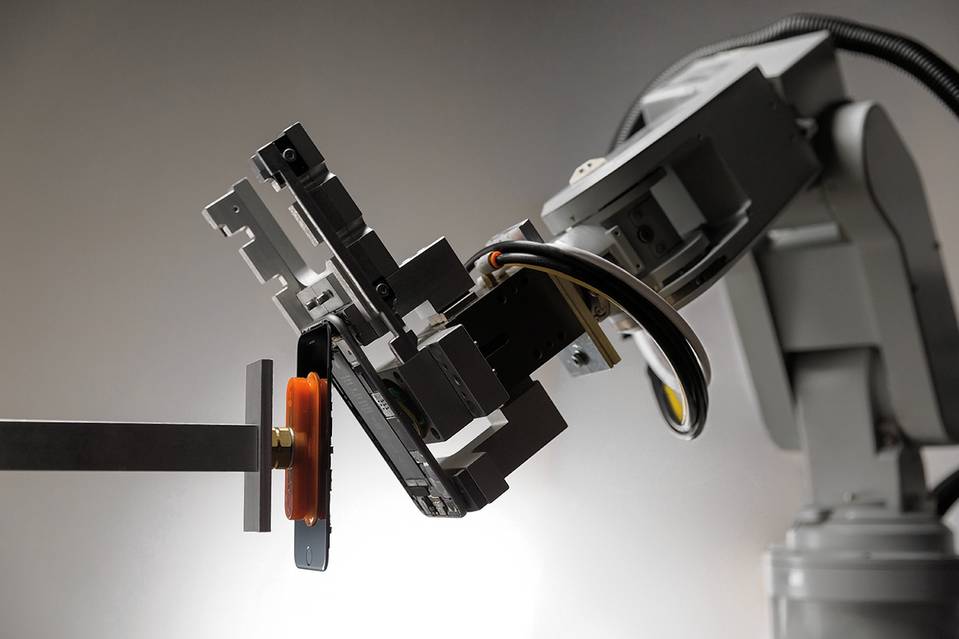

Apple introduced a piece of technology recently that will likely never be used by any consumer. Instead, it kind of cleans up after them: a robot that breaks down iPhones for recycling.

The arrival of Liam—a 29-armed robot capable of taking apart 1.2 million iPhones a year—speaks to a big challenge facing tech manufacturers today. Even as they strive to entice consumers to ditch their existing devices for the next new thing, companies must figure out what to do with the growing numbers of devices that are destined for the scrapheap as a result.

“We think as much now about the recycling and end of life of products as the design of products itself,” says Lisa Jackson, Apple’s vice president of environment, policy and social initiatives.

The company spent more than three years building Liam, of which there are currently two. Each carefully separates iPhone components such as the camera module, SIM card trays, screws and batteries. Instead of tossing the whole device into a shredder—the most common form of disposal—Liam separates materials so they can be recycled more efficiently.

Other electronics makers take a different recycling approach, designing products that simplify disassembly by replacing glue and screws with parts that snap together, for instance. Some also have reduced the variety of plastics used and avoid mercury and other hazardous materials that can complicate disposal.

Samsung Electronics Co. designed a 2016 model of its 55-inch curved television for easier disassembly. Samsung says it eliminated 30 of 38 screws, replacing them with snap closures. Now the TVs can be dismantled in less than 10 minutes, the company says.

It’s all part of the electronics industry’s efforts to undo a problem of its own making. The technological advances that replaced typewriters with personal computers, flip phones with smartphones and clunky TVs with flat-screen displays also spawned the consumer expectation that today’s cutting-edge product will become obsolete in a few years. The constant churn of new devices has contributed to an increase in electronic waste, some of which ends up in developing nations where local residents must deal with the health and environmental risks.

“Many of the environmental problems are made during the design process,” says William Bullock, a professor of industrial design at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and a faculty member at the Illinois Sustainable Technology Center. He says a product’s design choices for the types of materials and varieties of components are critical.

Industrial designers at Dell Inc. started meeting with recyclers about 10 years ago to think about how to design their PCs and laptops with the end in mind. Today Dell encourages the use of modular design with removable parts that can be fixed or upgraded to extend the life of a product. And when Dell uses more than 25 grams of plastic, it marks the type of polymer on the part to aid recovery and sorting. “If you don’t think about it at the beginning, with the design, it becomes a lot more complicated later on,” says Scott O’Connell, Dell’s director of environmental affairs, who works closely with product development.

Currently, 24 states have laws requiring electronics manufacturers to take back their products for disposal. Depending on a product’s condition, either the manufacturer or a hired recycler will refurbish it for reuse, or dismantle it for recycling where possible—separating plastics, base metals, precious metals and batteries.

The result is that while Americans throw away more consumer electronics than they did 15 years ago, more gets recycled. In 2013, Americans disposed of 3.14 million tons of consumer electronics, largely flat since 2009 but a major increase from 1.9 million tons in 2000, according to the Environmental Protection Agency. About 40% of those discarded electronics were returned for recycling in 2013, compared with about 19% in 2009.

Part of the motivation for manufacturers to support recycling stems from growing consumer concern about electronic waste. In a 2014 Harris Poll of roughly 2,000 U.S. adults, 86% said they wished manufacturers would design products for easier recycling. They also said they’d spend an average of 10% more for a product if they knew it was made from recycled materials.

Also, commercial customers like the U.S. government weigh the environmental impact of manufacturers’ products as part of the bidding process for computer and other equipment contracts.

Manufacturers say using their own recycled materials is less expensive than buying them elsewhere. Dell says plastic resin from its own recycling program can be up to 10% cheaper than buying recycled plastics from the open market.

Apple says for now it is focusing more on its recycling process than on designing its products for easy recycling. Liam, for example, is programmed to separate materials with great precision so they can be recycled at the highest possible purity and quality. So far, however, Apple says its recycled materials don’t meet the standards required for use in its products. The company won’t say what’s next for Liam. But Ms. Jackson notes that more iPhones will soon reach the end of their lives. “We want to be ready when our products start to come back,” she says.

Article Written By: Daisuke Wakabayashi of Wall Street Journal

0