Did Facebook Just Deliver A Crushing Blow To Native Advertising?

What looked like a small change to how media companies can share stories could have a huge impact.

Everyone assumes that if Facebook were to drop an anvil on media companies, it’d come in the form of an algorithm reconfiguration, a change in the revenue split on Instant Articles, or some combination of the two.

But for the increasing number of publishers that rely on native advertising to make ends meet, Facebook may have already delivered a brutal blow.

It all started with a seemingly innocuous announcement on April 8. In a blog post, Facebook announced that it would start allowing publishers to share native ads right on their Facebook pages. Most of the press treated this as a good thing for media companies, which could now promote native ads to their sizable Facebook audiences.

In reality, the news opened up the potential for disaster, due to a new tool Facebook just put in place.

THE TAG

For publishers, sharing native ads (or “branded content,” in Facebook parlance) now comes with a caveat: They have to tag the brand in the post, like The Onion did here while sharing a native ad for Firehouse Subs:

When a publisher tags a brand, that brand’s marketing team gets access to the post’s insights, which means they can see metrics like reach, clicks, and cost per click (CPC) if the publisher turned the content into a “sponsored post” to promote it to a larger audience. The brand could even pay to turn it into a sponsored post itself, using a new tool called Handshake.

The upside for Facebook is clear. They improve the Facebook experience by ensuring that users know when a publisher shares a piece of branded content, and they give brands a way to pay to promote posts they might not have previously. But that presents two big problems for publishers.

THE SMALL PROBLEM: AD EFFECTIVENESS

While publishers technically couldn’t promote branded content on their Facebook pages in the past, they got away with it by setting up Facebook pages for their content studios and sharing branded content there.

For instance, here’s the T Brand Studio page for the New York Times:

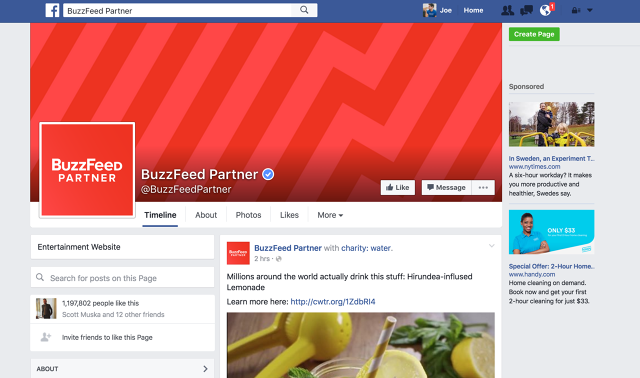

And the BuzzFeed Partner page for BuzzFeed’s native ads:

Until April, these pages could share their work without mentioning the brand, like T Brand Studio did for this native ad with Goldman Sachs. There’s no way you’d know that this was a native ad or that Goldman Sachs was involved.

Here’s another example, from a BuzzFeed post for Chrysler, 10 days after the change was announced in April. There’s really no way to know if this is branded content.

Basically, publishers could share native ads from these pages without revealing that they were native ads. And they could also create identical ads for the sponsoring brand—so-called “dark posts,” which appear in users’ feeds as ads but don’t show up on the publisher’s Facebook page.

According to financials leaked to Gawker last August, BuzzFeed was doing this a lot. The viral publisher spent roughly $1 million a month boosting native ad campaigns on Facebook in the first half of 2014, a figure that’s surely risen as BuzzFeed’s native ad business has since doubled. Hell, BuzzFeed has run so many ads that more than a million people like the BuzzFeed Partner Facebook page. In fact, some advertisers hire BuzzFeed just for its paid Facebook distribution prowess.

Most publishers have copied this model, spending a ton of money to distribute branded content via Facebook ads. But now that publishers have to tag the brand and explicitly acknowledge that they’re sharing branded content, there’s a very good chance they won’t be nearly as effective as the more deceptive system publishers were using before. This transparency is undoubtedly a good thing for users. But it that could cut into margins on native ad campaigns.

But there’s a bigger problem that could cut into publishers’ native ad margins even more.

THE BIG PROBLEM: THE BROKEN ILLUSION OF NATIVE ADVERTISING

Many publishers sell native advertising packages—which often start at six figures at prestigious outlets—by offering the unique opportunity to access their awesome/bespoke/high-value audience. But almost every publisher needs to buy traffic from Facebook and other outlets to support all of their native advertising campaigns.

If a publisher can create branded content cheaply and bundle it with inexpensive clicks from Facebook ads, it can make a pretty sweet margin on a native ad campaign.

Facebook may now ruin that.

As I noted earlier, Facebook’s new tag will allow brands to access all of the insights on a Facebook post or ad that they’re tagged in. As a result, brands will be able to see how much traffic to native ads comes from Facebook ads rather than organic website traffic. That could break the illusion that marketers are buying access to a publisher’s sacred audience. Instead, they’re just getting Facebook users who may or may not be regular readers of that publication.

Facebook’s tagging requirement will also allow savvy marketers to calculate just how big a margin publishers are taking on these campaigns—and potentially walk away feeling like they’ve just been ripped off.

Regardless, publishers will have to be very transparent about where the traffic to native ad campaigns comes from, and how much they’re paying for it. BuzzFeed and the New York Times, to their credit, already report paid distribution figures in details to brands. The Times even provides a live campaign dashboard that allows brands to see the sources of traffic, according to Lauren Reddy, T Brand Studio’s associate director of audience development. They also split out content creation and distribution as separate line items.

“This transparency helps partners decide where to scale up their investment to best hit their brand goals,” Reddy told me in an email.

However, the transparency that Facebook tags now provide will be very tricky for publishers who aren’t as advanced as the Times or BuzzFeed, and simply report top-line numbers to brands.

“Brands are going to start to understand how much of the reach is organic versus how much is paid,” said Alex Magnin, CRO of Thought Catalog. “That could change the equation in terms of how they look at the price that they’re paying to a publisher for a piece of content, how they value that content, and it could be a good thing or a bad thing for publishers depending on how valuable the publisher brand is.”

Publishers that are lumping in all of the performance metrics for their campaigns could be in for a rude awakening—and a few pissed off clients. And some think that’s been Facebook’s plan all along.

HANDSHAKE OR A STAB IN THE BACK?

In recent months, several people in the marketing industry have floated an intriguing theory to me: Facebook didn’t just introduce this tag for transparency and the good of the people.

Instead, it wants to lift back the curtain and show brands that publishers are just buying cheap clicks from Facebook and charging a huge premium. Subsequently, savvy marketers will realize what’s happening and that they can just pay publishers a fraction of the cost to create content, take distribution into their own hands, and get great results by spending all that saved money with Facebook directly.

Brands win by spending their ad dollars more efficiently, and Facebook wins by cutting out the middleman. Publishers, however, will be left without a key revenue stream. Or so the theory goes.

Magnin, for one, is very skeptical of this theory. He doesn’t think that advertisers will be surprised or bothered to see just how much publishers have been buying the audience to native ads from Facebook. He also argues that the value of a publisher’s clout will allow publishers to spend money more effectively than a brand could.

Take this hypothetical situation from Magnin:

“The brand might push that piece of content out on their own channels and spend a budget on Facebook to do so, and they might achieve a seven cent cost per interaction. But . . . because of the publisher’s trust with the user, the publisher might be able to achieve a three cent cost per interaction. That puts the publisher in a pretty strong position to say, ‘Hey, I’m creating a big chuck of value here. That’s why this works for me.'”

Still, advertisers could get the best of both worlds by simply waiting for publishers to share the post on their Facebook page and then boosting it on their own using Handshake, Facebook’s new tool.

It’s still unclear how all of this will work out. But Facebook has likely delivered a financial blow to media companies by shaking up the native ad model, and potentially revealing some iffy practices.

I’d say this is a game changer, but really, it’s just running up the score.

This post originally appeared on Contently’s The Content Strategist. Joe Lazauskas is the editor-in-chief of Contently and a marketing and technology journalist. Follow him on Twitter for media analysis and bad puns.

0